Jewish Chicago Magazine/

-

Tackling your genetic health, with support

The Norton & Elaine Sarnoff Center for Jewish Genetics launches hereditary cancer testing

Read more

-

Shabbat: It’s good for you! More than a day unplugged

Shabbat is still a revolution in our relentless age of screens and connectivity.

Read more -

A different kind of b’mitzvah

Nontraditional ceremonies and celebrations show there’s no single way to mark the milestone

Read more -

On the Town

Explore by Category

Browse the JUF magazine

-

-

Advice to my 13-year-old self

One of the best things about getting older is growing more comfortable in our own skin

Read more -

-

-

Dynamic duo Jamie Diamond Schwartz and David Schwartz named 2026 Annual Campaign Chairs

Jamie and David are first married couple to serve in this role

Read more -

-

-

-

Returning from the dark: Cancer & war

My entire life shifted and was redefined and reshaped that fateful July.

Read more

-

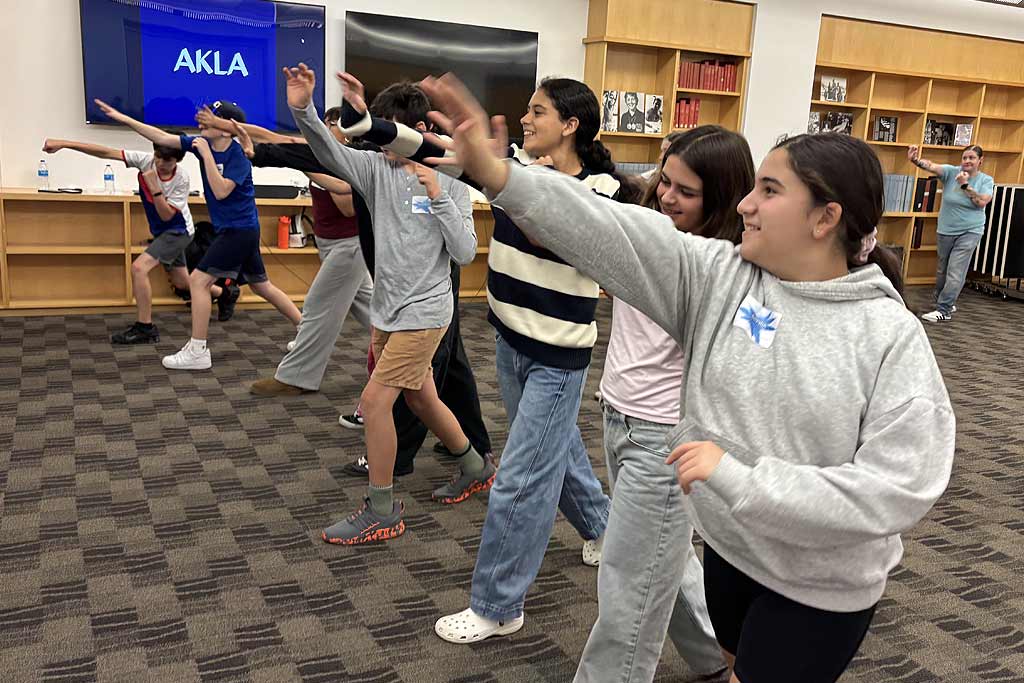

An ‘awesome’ new fellowship for teens

AKLA Chicago will be a free, five-week experiential experience for ages 12–14

Read more -

-